English 430

Recently I’ve been playing over and over in my head an experience from college that has become one of those “what-if” moments the older I get. I had taken a creative non-fiction course the last semester of my senior year, just months before I would graduate with a degree in literary criticism. I’d never been that excited about memoirs and biographies, but since I had already done poetry, creative writing--even a scifi/fantasy writing course--I enrolled in English 430.

The course was designed to teach us how to implement creative writing techniques in non-fiction pieces to enrich the storytelling of the content: using descriptive language, getting explicit with location details, authentic dialogue etc. Twice in the semester we were each put on the hot-seat, the assignment being all students would print out your short story, read it, and come to class ready to evaluate you. If you were “it” you sat through forty-five minutes of critique culminating with the professor's comments. This critique session was intimidating not only because a dozen or so other college students were shredding your writing, the content was usually personal since we were encouraged to draw on first-hand experiences.

One of the stories I had written was a piece called Things are Tight which documented a particularly unique Christmas I had had growing up. Money had been very lean that year, despite my mother’s legal profession, and we were told that there wasn’t going to be much in the way of presents or a tree. But what had been disappointing news, turned into the most memorable holiday of my childhood. The story included glimpses into my childhood imagination and was a vignette of life as the daughter of a single mother doing everything she could to give my sibling and me the very best. I was in tears when I had finished writing it, which was a sign enough that I had created something special. I saved, sent, and crossed my fingers knowing that my cohort would soon read it for themselves.

I agonized over the upcoming hot-seat. I told myself one hundred times how childish the story was. How immature it was to describe imaginary games of cats and trips to Fleet Farm, how getting five-hundred business cards with Cool Cat Club on them was hardly worth writing a short story about. The anxiety I felt as I entered class that day was leaving me lightheaded and ready to bolt in case I cried.

But as the critique began, I slowly realized my fears were misguided. I can’t remember exactly what was said, but most of the class (if memory serves) indicated that they had greatly enjoyed the piece and had little in the way of suggestions for improvement. The true test was my professor, whose comments that day I have never forgotten: She told me she had no advice. She told me that Things are Tight could be sent for publication that very day if I wanted.

A smarter, perhaps more courageous, person would have ended class smiling ear to ear and would have gone to the professor to ask for suggestions for submissions. Instead twenty-three-year-old me nearly ran from the room, found a bathroom, and cried anyway--in shock and in disbelief.

I guess the shock has finally worn off over the last decade, and I’ve decided to try my hand at publishing Things are Tight. And despite the feedback from my classmates and professor--I’m going to mature the piece before I send for submissions. I like to think I’ve grown as a writer since my undergrad.

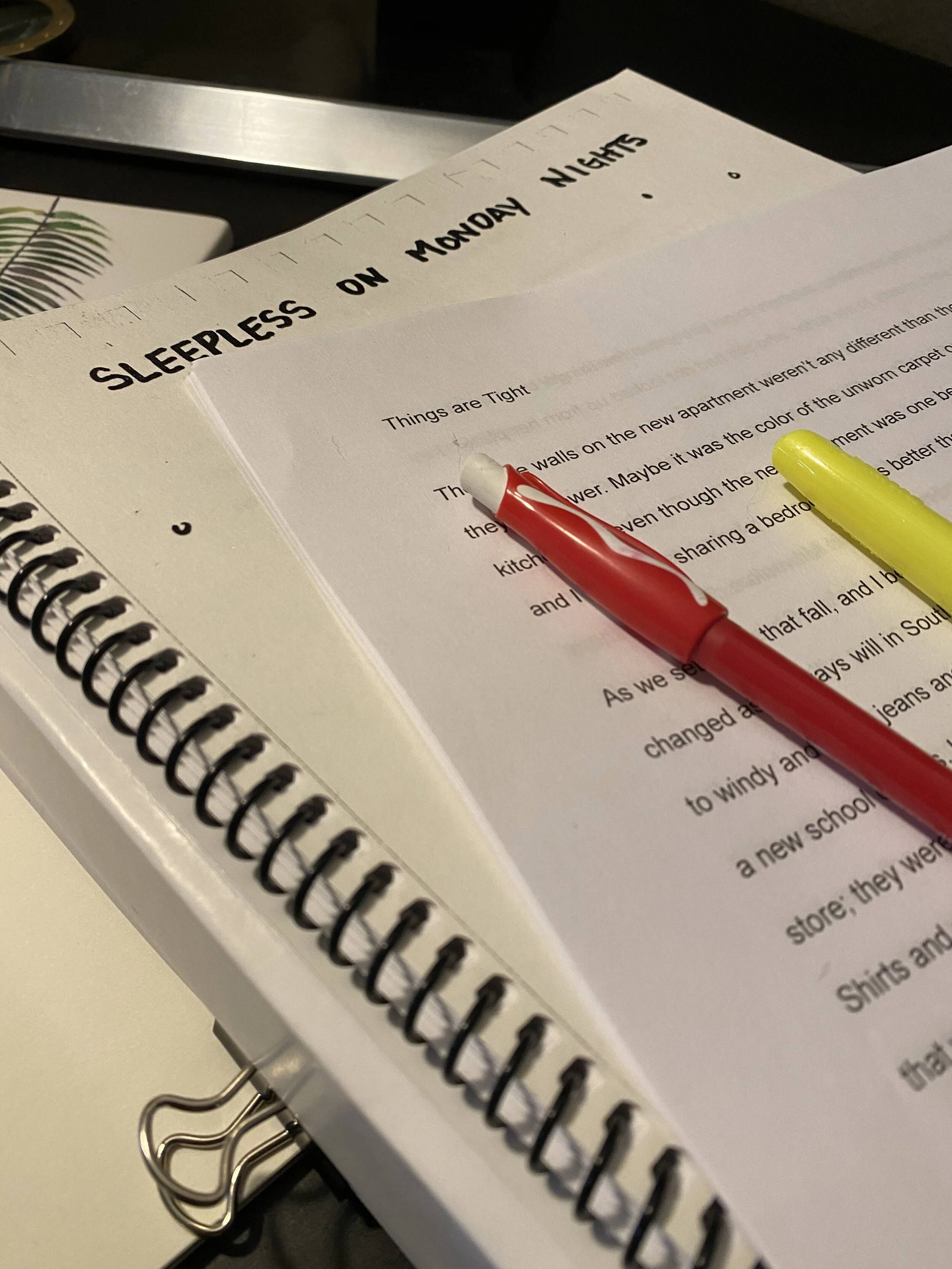

But where to start? How do you take a decade-old piece and grow it up? The first step was to transcribe the piece since it only existed in a printed anthology, Sleepless on Monday Nights, that my professor gifted our cohort that year. Then I had to read it. Read it again. I could see that the content was there: the piece has characters, it has a beginning, middle, and end, and it has dialogue and vivid location. But it was missing something--or somethings--I could not put my finger on.

So I did what I always do with a piece I’m stuck on--I hibernated it. But would another decade go by before I knew where to take my piece?

It just so happens that I have a dear friend who reached out and asked me to provide some developmental feedback on an article she has been writing. The article is very thought provoking--dealing with brain chemistry and political leanings as they relate to the up-coming election. She knew already that some areas were under-developed, but wanted to know if I had any suggestions. The first thing that stood out to me were the headings she was using to break off sections of the nearly 3K word essay. She was right to break up the information since the content would ultimately be consumed on the internet. But were the headings in the right places? Did they capture the content they represented correctly?

Once I finished a first pass on the piece, I realized what I needed was an outline. I had learned about Reverse Outlining in my editing certificate course, but had not had use for it in the projects I had been working on up to that point. I started again at the beginning of the article and slowly filled in an outline based on what my friend had written. And looking at the completed article in list-form--I suddenly knew what developmental advice I could offer with regards to the article. I could see where the article needed more content, what content was out of place, and saw the flow of her idea. I wrote up an email with my critique and sent it off to my friend.

Now staring at my desk after a successful developmental edit, Things are Tight beckoned to me from the corner of my table. In an effort to inspire any kind of developmental progress on my own piece, I had printed out the short story. There it sat, patiently waiting for me to highlight, underline, and make comments to myself in the margins. And as I looked at the words on the page, and feeling the excitement of having unlocked the perfect way to edit for my friend, I asked myself why I couldn't also create an outline for my own short story.

While my short story didn’t have headings, it did have scenes. Though they are short, they are in themselves made up of tangible parts. A description of the apartment we lived in, the night our mother told us that “things were tight,” a conversation between my sibling and I about what it all meant. And once I could see what I had, I could see what I was missing--and what would enrich the piece. A look at what it is like to live in an apartment your whole life, an explanation of why a lawyer might be cash-poor, the rearrangement of events to more linear places in the piece.

“…once I could see what I had, I could see what I was missing…”

Editing can sometimes be as daunting as staring at a blank page on November 1st, except that the words that you’ve already written are now your blank page, and you are here to--Change it? Fix it? Improve it? Editing block is its own impediment much like writer’s block, but without the freedom to just down a glass of whiskey, close your eyes, and write. You are challenged with needing to be tactical, calculated--to have a plan. A Reverse Outline can be the building block of that plan. A map of your work, a place of reference to see where you have already been as a guide to where you want to be.

And with that, the updating of my piece is underway. And although a decade has passed since that day when a twenty three year old ran from the room in tears, here’s to hoping Things are Tight (v. 2020) finally finds its home in a submission inbox, and perhaps if I am lucky, in print.